AI is already part of childhood

Whether we planned for it or not

AI didn’t arrive in children’s lives with a bang.

It didn’t come with a permission slip or a parent information evening. It didn’t announce itself as artificial intelligence.

It arrived quietly. Inside homework tools, social feeds, games, filters, chat functions and “helpful” features built into apps children were already using. For most families, it didn’t feel like a decision at all. It just drifted in.

Which raises an obvious question: what’s actually happening inside UK homes right now?

I surveyed UK 150 parents with children under 18. Here’s what I found.

Where children are encountering AI

For most families in this sample, AI isn’t confined to a single app or device.

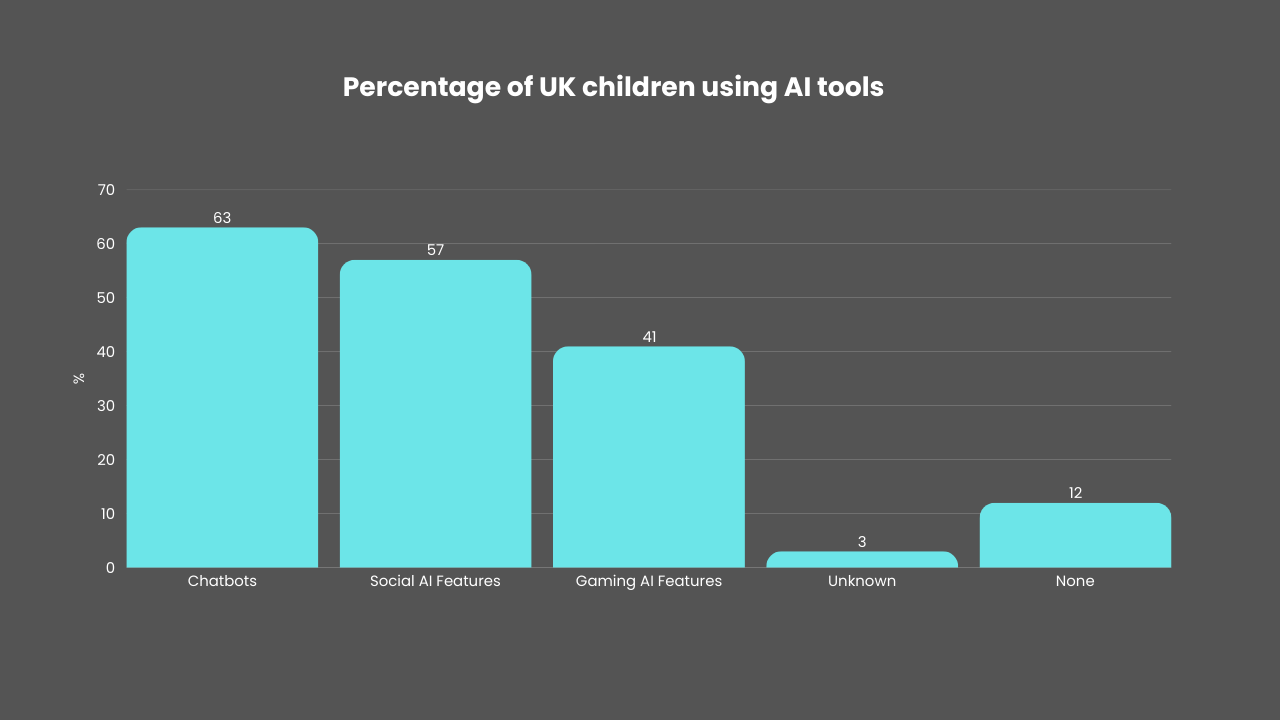

Around two thirds of parents say their child uses AI chatbots such as ChatGPT, Claude or Gemini. A similar share report their child encountering AI through social features embedded in apps like TikTok or Snapchat. Roughly four in ten say their child uses AI in gaming environments.

Only a small minority (12%) selected “none”.

The important detail here isn’t the specific tools. It’s the route of entry.

This tells us that children aren’t meeting AI through clearly labelled “AI for kids” products. They’re meeting it through mainstream platforms - the same ones parents already associate with schoolwork, entertainment and social connection.

For most children, AI is simply part of the digital background.

Children are using AI a lot!

This isn’t occasional experimentation.

Close to four in ten parents (38%) say their child uses AI tools daily. A similar proportion (37%) say weekly. Only a small fraction describe usage as rare or monthly, and around one in ten say their child never uses AI at all.

A noticeable group of parents (8%) say they don’t know how often their child uses AI.

Taken together, this suggests something important: for many UK children, AI is already a routine presence. Not a novelty. Not a future skill. A weekly - or even daily - habit.

How parents feel about it

Parents aren’t indifferent.

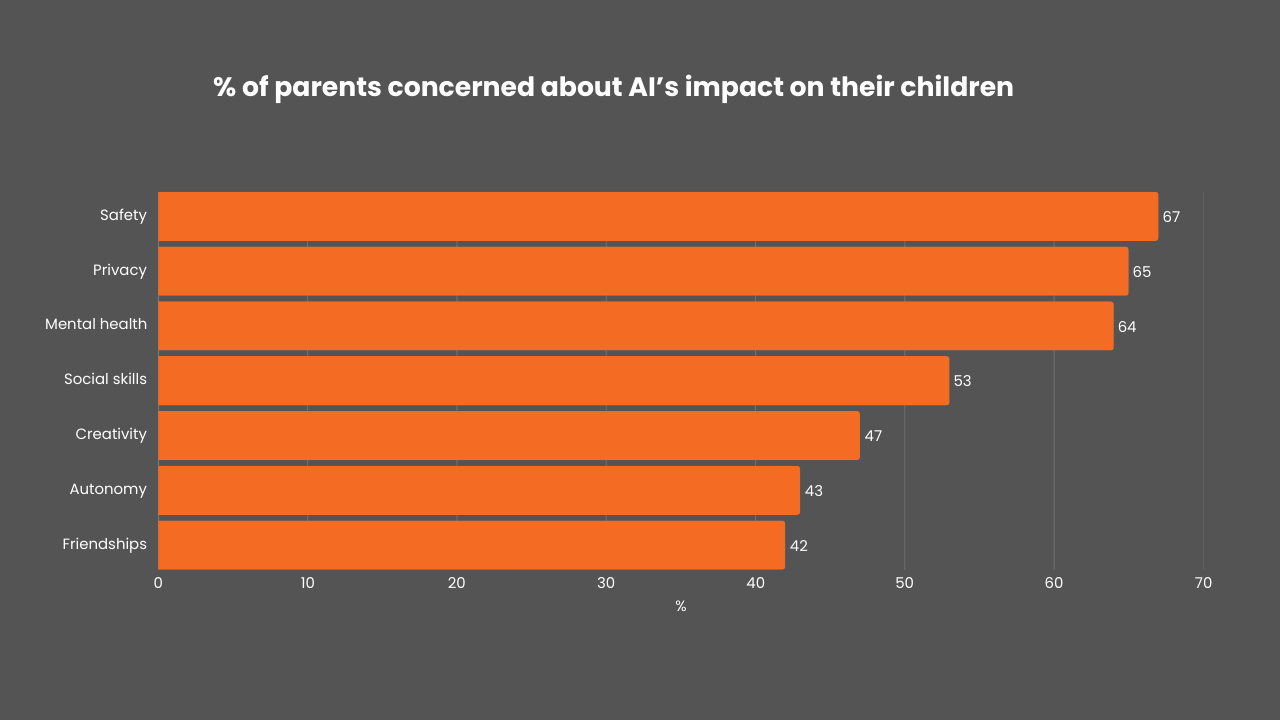

Across privacy (65%), safety (67%), mental health (64%), creativity (47%), social skills (53%) and autonomy (43%), substantial numbers express concern. Nine percent have already encountered or strongly suspect a negative AI-related incident involving their child and 31% believe AI has already impacted their child’s development.

Yet alongside that concern sits something else: excitement. Almost half of parents (49%) say they feel excited about the future impact of AI on their child.

Parents appear to be holding two truths at once: AI looks like an opportunity their child shouldn’t miss - and a risk they don’t yet feel fully equipped to navigate.

Hey Reader. A ❤️ goes a long way!

What children must understand, whether schools teach it or not

When you sit with this data for a moment, one thing becomes clear.

AI is no longer a specialist topic. It’s not something children encounter once they’re “ready”, or once the curriculum catches up. For many of them, it’s already woven into how they learn, play, communicate and explore the world.

That means some foundations can’t be optional. They can’t depend on whether a particular school covers them well, or whether a platform decides to explain itself honestly.

There are a few things every child now needs to understand about AI - early, clearly, and repeatedly.

Who do you know who needs to know this? Please share this piece with them!

1. Seeing is no longer believing

Children should be taught, as a non-negotiable, that images, videos and audio can be convincingly fabricated by AI.

Not just edited. Not just filtered. Entirely invented.

That includes faces, voices and situations that look and sound real but aren’t. If we grew up learning to trust our eyes and ears, our children have to learn the opposite: that realism is no longer proof.

This isn’t about paranoia. It’s about baseline digital survival.

2. Their data is not “just data”

Children need to understand that their image, voice, location, creative thoughts, writing style and behaviour are part of who they are.

Their data is a kind of digital body.

Once it’s shared - especially with unknown apps, games, quizzes or chat tools - it can be copied, stored, analysed and reused in ways they don’t control. “Delete” doesn’t always mean gone. “Private” doesn’t always mean private.

This has to be taught early, before habits form.

3. Parents can be cloned - so checks matter

This one is uncomfortable, but essential.

Children should know that voices and messages can be convincingly faked. That someone can sound like a parent, a teacher or a trusted adult - and still not be them.

Every family should have a simple, agreed way to verify urgent requests. A safeword. A second channel. A pause-and-check rule.

Acting on a voice or message alone should never be enough.

4. An AI answer is not the same as a Google result

Children need to understand the difference between search and AI.

Search tools show you sources. AI tools generate answers by predicting what sounds right based on patterns in data. They can be helpful - and they can be confidently wrong.

AI doesn’t know when something matters. It doesn’t know when to slow down. And it doesn’t take responsibility if it misleads you.

Anything important should be checked with trusted humans or reliable sources.

5. These tools are designed to influence behaviour

This may be the most important lesson of all.

AI systems are not neutral. They’re built by companies with goals: to keep attention, encourage use, collect data and shape behaviour. Friendly language, reassurance and personalisation are design choices - not signs of care.

Children should learn to notice when something is trying to rush them, flatter them, scare them or make them feel left out. Urgency is often a signal to pause, not to act.

6. Boundaries matter more than cleverness

Using AI well is not about being the fastest or most advanced user.

Children need clear boundaries around what should never be shared with a tool: home address, school details, live location, passwords, intimate images, or anything they wouldn’t say to a stranger in a room.

If something feels strange, upsetting or confusing, the first step isn’t to hide it or handle it alone. It’s to screenshot, pause and tell a trusted adult.

This isn’t about raising anxious children or banning technology. It’s about giving them a mental framework that lets them use powerful tools in a way that benefits them.

If you’re a parent, I’d love to know: what worries you most about AI and your child right now?

Thanks for sharing these. Interesting results and I appreciate the suggestions. Do you have any split by age range for “under 18”?